Non-competition agreements (sometimes referred to as restrictive covenants in Louisiana) have become a common condition for employment. At some point in your career, you may have unknowingly signed a non-competition agreement as part of the stack of paperwork handed out during new-hire orientation. A noncompete agreement can be a standalone agreement or a clause or attachment in a longer employment agreement, is usually stringently worded, and often includes a threat of litigation should the employee breach one or more of the agreement’s terms.

So, why do employers force new hires to sign? Non-competes benefit employers in multiple ways. They discourage employees from leaving the company, as the agreements purportedly bar employees from working for direct competitors or going out on their own. The fear of getting sued by an employer for breaching a non-compete could help keep talent at the company. Non-competes also exist to protect a company's confidential and proprietary information, such as client lists, marketing strategies, manufacturing techniques, products development, and recipes.

Basically, a noncompete agreement is an attempt to restrict your employment opportunities after you leave your current job, regardless of whether you leave voluntarily—a prospect that may seem pretty scary. But, regardless of the strong language or threats from your current or former employer, the agreement may not be enforceable in Louisiana. Non-compete agreements are null and void in Louisiana and deemed to be against public policy, unless the non-compete clause or agreement fits within one of the statutorily recognized exceptions. A statutory exception exists for most employer-employee relationships, allowing an employer to prohibit a former employee from “carrying on or engaging in business similar to that of the employer” or from soliciting an employer’s customers. (see La R.S. 23:921). However, under this exception, an employer-employee non-compete agreement is enforceable only if it:

1.Expressly identifies the territory consisting of a parish or parishes, or municipality or municipalities, or parts thereof, in which the employer is operating, and

2.Does not exceed a period of two years from termination of employment.

Also, an employer cannot simply list all Louisiana parishes and call it a day. Enforcement is limited to parishes or cities where the employer actually conducts business and has a location or customers. These parishes or cities also must be specified within the agreement in a way that is clearly discernible to the employee. For example, a Louisiana court found that a contract with language stating “whatever parishes, counties and municipalities the Company...conducted business” was unenforceable because it lacked specificity as to which parishes were included and where employer did business.

As far as the activity the non-compete is attempting to restrict, Louisiana courts have emphasized that “the law does not require a specific definition of the employer’s business.” That said, a non-compete that includes overly broad definitions of the employer's business are likely null and void under Louisiana law. In one case, a Louisiana court held that a non-compete prohibiting a doctor from the “practice of medicine,” instead of specifying pain management, was overbroad and void. In contrast, another court held that a non-compete agreement defining a hazardous waste cleanup company’s business as including “waste transportation and disposal,” and further clarifying that the business was limited to “oil and hazardous spill containment,” was sufficiently narrow to enforce.

So what’s the takeaway? Non-competes are strongly disfavored in Louisiana, and courts are apt to interpret vague non-compete agreements in favor of employees and against parties attempting enforcement. Each situation and set of facts is different; however, a non-compete should not prevent anyone from furthering his or her legitimate career goals. If you find yourself in a situation where your former employer may enforce an existing non-compete against you, all is not lost. If possible, consult an experienced employment lawyer before leaving your job. Your attorney will help you come up with a plan to reduce the risk of you getting sued on the backend. If you already left and your former employer is threatening suit, immediately contact an attorney to protect your rights and defenses. Once an employer files suit, you may have little time to retain an attorney and discuss your case with that person. Enlisting the help of an experienced employment lawyer as soon as you know your employer is challenging your actions is the best way to protect yourself.

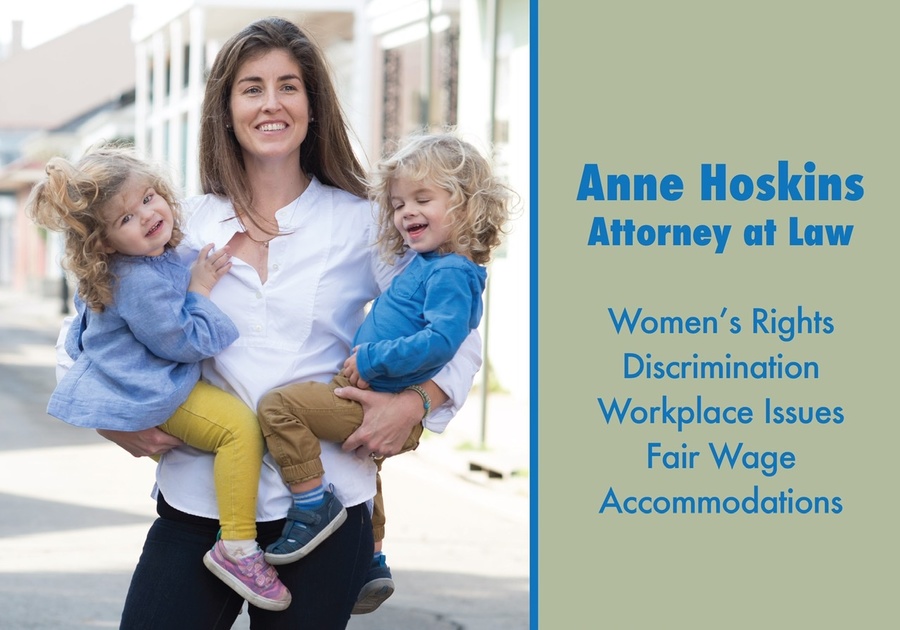

Anne Hoskins is an attorney who represents working women throughout Southeast Louisiana. If you have a non-compete issue, believe your employer is violating the law and/or adversely affecting your employment status, or have any other employment-related concerns, you can reach Anne at (504) 234-4672 or anne@hoskinsfirm.com.